Philip Pullman on Writing Myth & Religion

I thought it was a joke: Philip Pullman, young adult author and outspoken critic of organized religion, in a public discussion with, get this, the vicar in a church. So it’s okay to be organized in a church so long as the topic is writing.

I grabbed my teenaged son, who loved His Dark Materials trilogy even more then Harry Potter, and joined throngs of Oxford students at The University Church of St. Mary the Virgin on October 22nd. What a dramatic setting: stained glass, vaulted ceilings and gargoyles dating back to the 13th century. I half expected to find a daemon lurking in the pews. The fantasy series was set in his hometown of Oxford in this universe and in others.

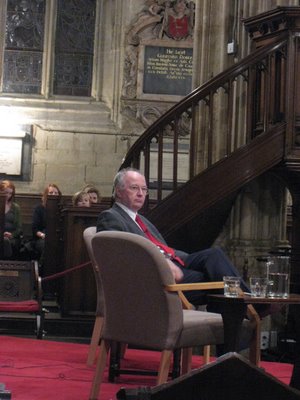

I grabbed my teenaged son, who loved His Dark Materials trilogy even more then Harry Potter, and joined throngs of Oxford students at The University Church of St. Mary the Virgin on October 22nd. What a dramatic setting: stained glass, vaulted ceilings and gargoyles dating back to the 13th century. I half expected to find a daemon lurking in the pews. The fantasy series was set in his hometown of Oxford in this universe and in others. Philip Pullman fitted the collegiate venue. He looked and sounded more like a tenured college professor than a bestselling author and iconoclast. He was warm and friendly with his host, Canon Brian Mountford.

Philip Pullman fitted the collegiate venue. He looked and sounded more like a tenured college professor than a bestselling author and iconoclast. He was warm and friendly with his host, Canon Brian Mountford. Pullman referred to himself as a “Church of England Atheist.” He praised the Bible for its beautiful prose and noted religion’s value in building community. Pullman’s quarrel is not so much with religion but that “the church abandoned people in my position.” He cited religious wars, persecution and intolerance.

The Church of England was an important part of his personal history. He seemed to regard it more like an eccentric relative than the enemy. When Pullman was only seven, his father died. His grandfather, an ordained minister, partially raised him. Pullman praised his beloved grandfather for being a gifted storyteller. Later Pullman claimed that parents could do better by telling moral stories as opposed to religious ones.

In a Hollywood minute, the conversation jumped from religion to the upcoming film version of His Dark Materials. When Mountfield asked if the adaptation was true to the book, Pullman replied that the film is but one in a long series of different ways of telling the same story. Since writing the novels, there have been abridged audio books, a radio dramatization and 2 stage plays. Each has a different emphasis that reflects the genre.

His Dark Materials film will have special effects not possible on the page. It won’t be the same because the book takes eleven hours to read out loud, compared to a two-hour film. Pullman also wrote some special scenes just for the movie.

What impressed me most was Pullman’s eloquence and lack of conceit. He seemed to see the writer as a tool in the process: “stories only come into being when you read them; you can’t tell the meaning.”

Pullman has no problem with readers having different interpretations or leaving questions unanswered. When writing, the author is a tyrant and the process is despotic. Once the book becomes published, it becomes a democracy of the readers. “Reading is engaged in silence and secrecy, and there is nothing I can do about it.”

Writing is still hard work. The Northern Lights (The Golden Compass in the USA) took Pullman seven years to write. It still isn’t faultless. “If you want to write a perfect piece of literature, write a haiku or a sonnet but don’t bother writing a novel.”

Nonetheless, Pullman appreciates the craftsmanship of forming sentences and the discipline of using words precisely. He frequently consults the dictionary and loathes clichés. His focus is as much on enjoying the medium of language as on telling the story. With experience writing gets both harder and easier. “It is easier because there are more ways to say the same thing, but it is harder to choose.”

What sets Pullman apart from most contemporary writers of children’s fiction are his literary references. His work draws heavily from the Judeo-Christian tradition and from John Milton’s Paradise Lost. His books resonate with the notion of fall and redemption. There is also a fair bit of science, including string theory, in creating his parallel universes and “dust.”

His Dark Materials leave readers of any age with questions. The biggest one is “what is dust?”

Pullman explained, “It is the visual analogue of all things known, all thoughts. What I call dust is what makes us what we are.” He avoided using the term soul but instead referred to the human “sense of consciousness.” The purpose of dust was “to develop a myth as a place to stand like in the Judeo-Christian tradition.”

I’m wondering how much of this will be clear to my ten-year-old daughter, who just started reading the series. To her, it is all about the daemons, those lovable animalistic beings that are the other half of humans. My daughter would calls them cute, little shape changers, but Pullman said they are the “aspect of oneself.”

Pullman claims that his best idea was having the daemons constantly changing form until their humans hit puberty. At heart, it is a young adult book dealing with this magical transformation from child to adult.

Biggest laughs came when Pullman answered the question of what would be his daemon. “My daemon would be a scruffy bird that steals from his neighbors.” He elaborated on how his imaginative fiction is rooted in research.

There is no doubt in my mind that his best character is the drunken, armored polar bear. Pullman created this creature and the dueling scene after reading an 1812 essay about fencing with a bear. His magic brings it to life.

The view from St. Mary's tower of Oxford

The view from St. Mary's tower of Oxford On the way out, we dropped a couple pounds in the church collection box. St. Mary’s also raises funds from visitors to the tower and by running a café called Vaults and Garden. The food is fresh and wholesome. Still, it’s hard to imagine any of this happening in an American church. That’s the fun of living abroad.

On the way out, we dropped a couple pounds in the church collection box. St. Mary’s also raises funds from visitors to the tower and by running a café called Vaults and Garden. The food is fresh and wholesome. Still, it’s hard to imagine any of this happening in an American church. That’s the fun of living abroad. A blog is the ultimate democracy of the readers. What’s your take on Philip Pullman’s mythology?

Labels: authors, books, England, movies, Oxford, Philip Pullman, restaurants, writing